by Larnaca Biennale 2023 curator Yev Kravt

Sometimes, when we’re away from home for too long, we suffer homesickness. It can be an odd, uncanny feeling. But what is it we actually miss when we’re homesick? Is it a house? The furniture? Our pets? Or simply the warm hug of safety and familiarity? The troubling context of a global pandemic, which at times left us isolated or unable to travel home, and which continues to steer the course of so many lives, has in itself urged a wider reconsideration of our immediate surroundings. Throughout my artistic research for the Larnaca Biennale, my hope is to tackle the theme – “Home away from Home” – from a variety of different perspectives. Among the theme’s many possible readings, both architecture and design become key areas for further thought.

In today’s globalised world, national identities seem to blend more than ever. Whether it’s in Dubai, Athens, Cape Town or Bangkok, we’ll find many of the same shops selling the same things; cafés offering the same coffee and cake; museums filled with those who share similar lifestyles, interests, and maybe even value systems. As monoculture peaks, and as global homogenization marches on, can we still imagine a dream home? What would it look like? Who does it borrow from? And does it correspond with our ‘true’ identity?

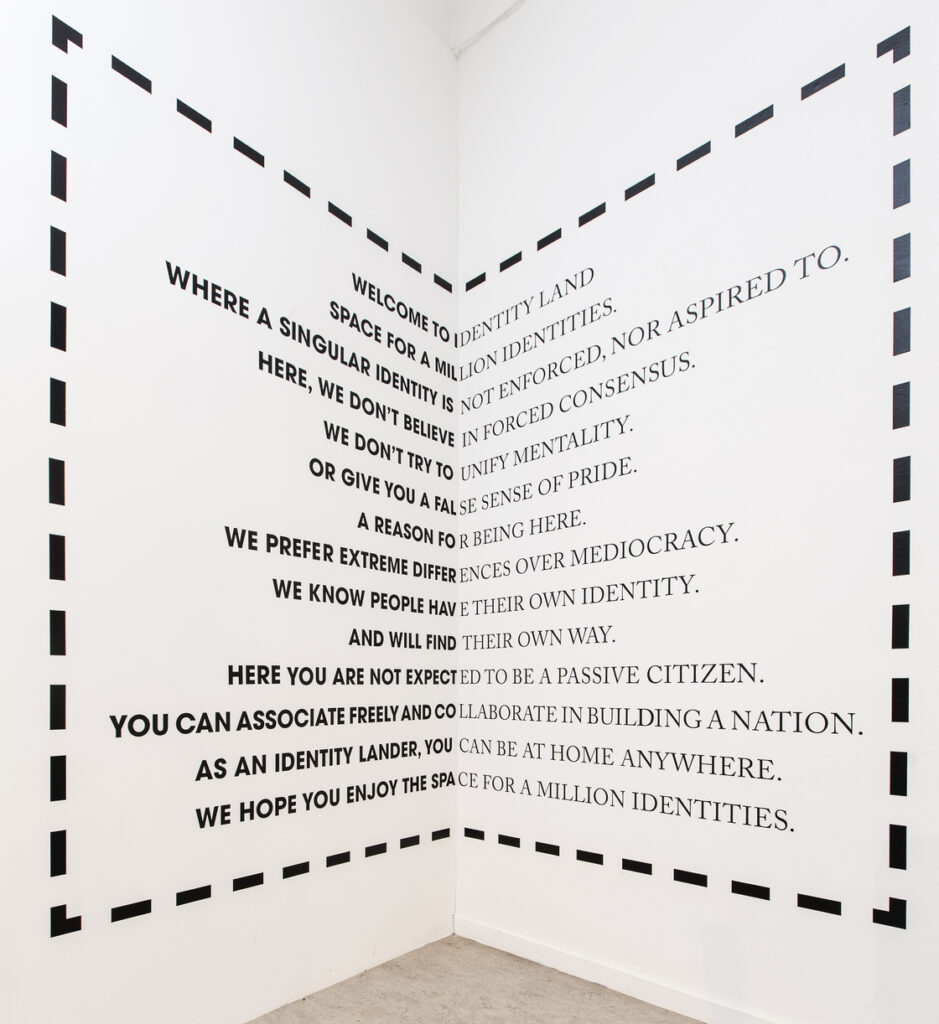

Take a place like Belgium, where some citizens struggle to pinpoint tangible examples of what makes them who they are. It’s a country of converging cultures: a hybrid people juggling three languages; a culture changed through centuries of rule by France, Spain, Austria and Holland; a society further transformed by more recent waves of immigration – namely from its former African colonies. Taking this ‘identity crisis’ as a starting point, the Dutch design platform, Droog, worked with artist Erik Kessels to proffer a creative solution. What emerged was Identity Land, a speculative space for a million identities. The project considers how designers and artists might better define what makes a people – from language and literature to currency, music and politics – when the conventions of national identity become obsolete.

Other future identities are dreamt up by the likes of Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez. His dazzling sculptures of imagined buildings and cities reflect the artist’s dreams for his country, his continent, and for the wider world. Kingelez’s “extreme maquettes” offer fantastic, utopian models for a more harmonious society of the future. It’s an optimistic counter-image to his own experience of urban life in the metropolis of Kinshasa. The “extreme maquettes” are not intended for building. They are art more than architecture, sculptures rather than working models. For Kingelez, art has the power to transform, to imagine, and to work towards a truly global society. “Art is the grandest adventure of them all,” he muses. “Art is a high form of knowledge, a vehicle for individual renewal that contributes to a better collective future.” A better home, too, perhaps?

In his book, The Architecture of Happiness, Alain de Botton wrote that “we tend to honour with the term ‘home’, those places whose outlook matches and legitimates our own. We turn to wallpapers, benches, paintings and streets to staunch the disappearance of our true selves.” In his eyes, then, happiness is no easier to find in architecture than it is elsewhere. Buildings of stone and steel rest on the fragile foundation of human emotions and confused desires. “Bad architecture is in the end as much a failure of psychology as of design,” he writes. “It is an example expressed through materials of the same tendency which in other domains will lead us to marry the wrong people, choose inappropriate jobs and book unsuccessful holidays: the tendency not to understand who we are and what will satisfy us.”

With a dose of humour, de Botton’s reflections underline our need for home in the psychological sense as much as in the material sense. We need a refuge to shore up our states of mind, and for our rooms to align us with desirable versions of ourselves – to keep alive the important, evanescent sides of us. The work of Bea Camacho, an artist from the Philippines, deals with ideas of isolation, shelter and camouflage. The Enclose performance saw the artist crochet herself with lengths of yarn into a red cocoon – she wraps herself until the point of disappearance, her body concealed by the nest she creates. Contemplating notions of security and comfort, Camacho’s work ponders distance, ephemerality and fragility, and the primal feeling of being safe.

Our relationship to home is deeply linked to a sense of wellbeing. It’s certainly a very personal feeling. One of the miseries of homesickness, however often overlooked, is a longing for the things that surround home – be it a city, a country, the surrounding streets, the landscape and the built environment, the familiar smells that envelop it. The things that fill it are equally significant; each object reflects private histories, or is imbued with social value. Preoccupations with the particularities of architecture and design are often condemned as frivolous, or even self-indulgent. But what if our love of home is a way to acknowledge an expanded, complex, personal identity – one forged in community, brief memories and minute details? Artists, architects and designers each have a powerful role to play in reimagining the role of domestic spaces, just as they can turn up essential new visions for what a broader, better community might look like. To me, that duality is the essence.